Beeple’s Diffuse Control is an image-generating sculpture that invites visitors to collaborate with artificial intelligence. A custom website allows museum visitors to interact with the AI generative system, which transforms images of select public domain artworks from LACMA’s permanent collection, organized in five iterations. The sculpture—comprising 12 large video screens—displays the resulting images, allowing the audience to remix this new creation in real time. Diffuse Control by Beeple is on view through January 4, 2026.

Here, Jordan David, Cameron Schrier Foundation Fellow, Chinese and Korean Art, reflects on artworks selected for the iteration Soft Jelly.

The six artworks included in the iteration Soft Jelly focus on the human and non-human body in motion. Each piece was chosen to examine how the collaboration between the sculpture’s generative algorithm and audience input would alter a figure's direction, placement, and composition, seeking to understand the evolving relationship among body, audience, and AI throughout the duration of Diffuse Control at LACMA.

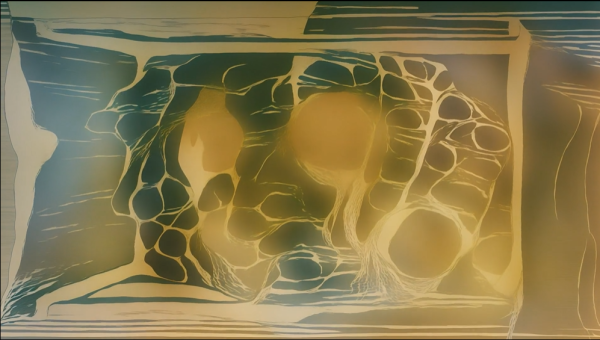

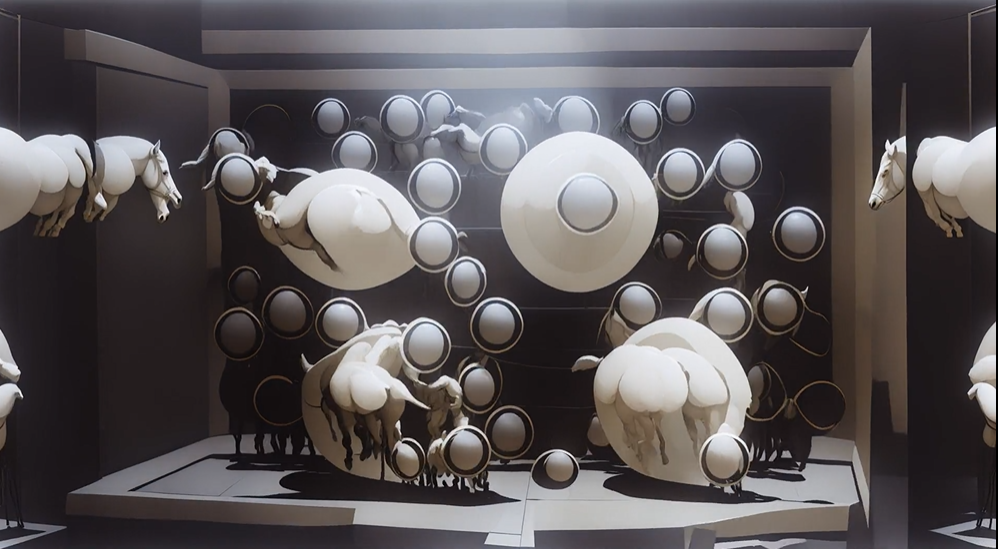

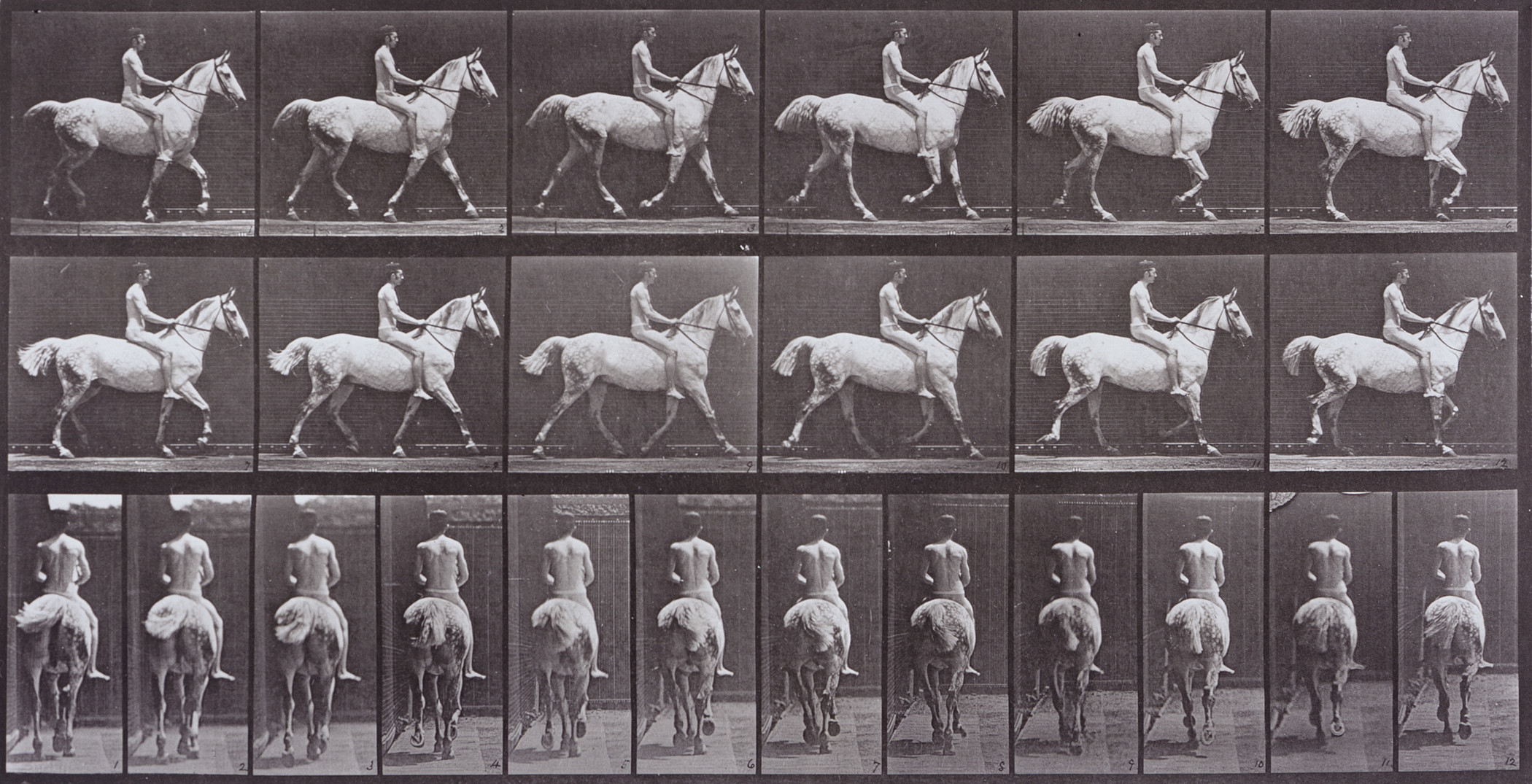

Some works, once rendered in Diffuse Control, dissolve into abstract compositions, like Edvard Munch's green and teal woodcut Head to Head (1905), which starts as a pair of heads nuzzled into one another that transform into a swirling scene of shapes, lines, and colors, losing any trace of its original figural components. Unlike Munch’s work, the black-and-white horses in Eadweard Muybridge’s collotype Animal Locomotion (1886, printed 1887) still retain most of their equine form, giving the once-stagnant animals actual movement.

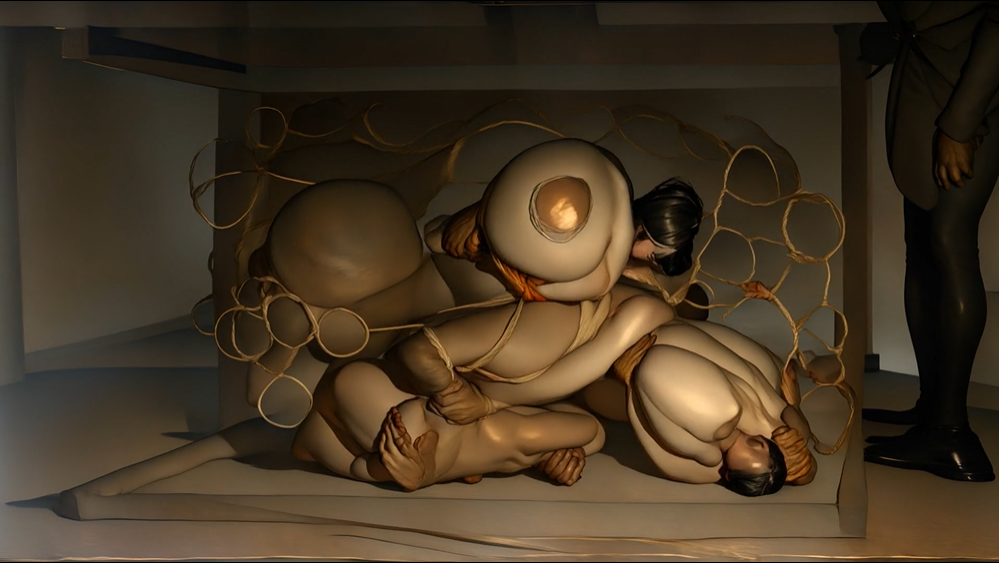

The first work in the iteration, Thomas Eakin’s oil painting The Wrestlers (1899), on the other hand, becomes considerably more monstrous compared to the other pieces, as the already entangled, pale-skinned wrestlers are further infused by the AI algorithm, even combining with the background characters, essentially creating an expanding, digital blob of flesh. One can make out limbs, hands, and heads, but not who they belong to.

The grotesque malleability of the figures once in the generative AI system directly inspired the iteration’s title, Soft Jelly. The name alludes to the ending of Harlan Ellison’s seminal 1967 science fiction short story “I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream,” in which Ted, the last human on earth, is transformed into a sentient and mute “soft jelly” creature for eternity by the antagonist of the story, an all-powerful, evil supercomputer named AM, as a punishment for the deaths of his other prisoners. In the very last page of the story Ted reflects internally on his wretched state unable to vocalize his anguish: “Rubbery appendages that were once my arms; bulks rounding down into legless humps of soft slippery matter.” The six works in this iteration, too, become a “soft slippery matter,” blending into each other and forming a single, gooey, pliable entity ready to be molded by the museum visitor.