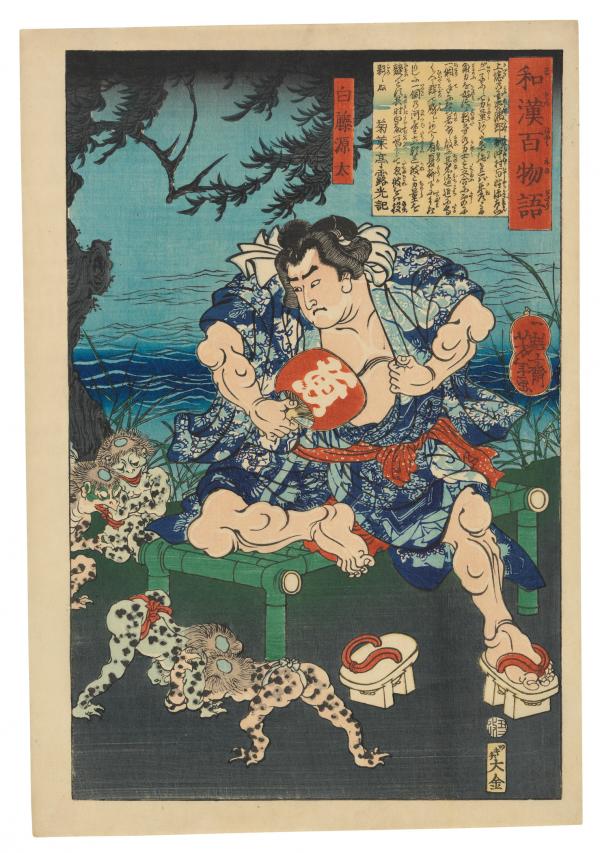

Any visitor to Japan quickly discovers that animals are everywhere. They are present in high art and low, in religion and popular culture, in objects made for the tea ceremony, and even as symbols for the times of day. Animals have long inspired Japan’s creative imagination and continue to do so today to a remarkable degree.

Why is this so? The answer requires an exploration from multiple perspectives. The religious practice native to Japan, Shintō (“the way of the kami,” or spirits), with its worship of divine powers manifested in nature, is a logical starting point. In Shintō, certain animals, such as deer or foxes, are regarded as messengers of the kami, while other animals, such as monkeys, can serve as their representations. The sacred horse (shinme)—the preferred mount of the kami identified with Shintō shrines—is sometimes depicted with its grooms costumed as priests or attendants. In Shintō belief, one prays to a black sacred horse for rain and to a white one for the rain to end.

Although today some think of Shintō and Japanese Buddhism as separate and distinct, this is hardly the case. Sculptures of Buddhist deities may be enshrined adjacent to Shintō kami, and Shintō shrines may be located on the grounds of Buddhist temples. Indeed, representations of certain animals, such as the fox, can be seen as either Shintō or Buddhist, or both, depending on the context.

In Buddhist art there is a long tradition of depicting the transience of beauty and our mortal existence. Izumi Magouemon’s sculpture of a skull and snake, carved from a single block of boxwood, may have been seen as a distinctly Buddhist, animal-themed memento mori. From the Buddhist perspective, this juxtaposition of human skull and animal might serve as an object of contemplation for those striving to be free from attachment to the physical, temporal realm. Yet the artist also intended this sculpture for a Western audience because he submitted it to the Chicago world’s fair of 1893, where it won a prize.

The inspiration for the exhibition Every Living Thing: Animals in Japanese Art, (on view through December 8, 2019), came to me when my friend and colleague, the distinguished Japanese art historian Itō Shirō, remarked that I might be seen as a zookeeper rather than a curator because the Pavilion for Japanese Art at LACMA displays so many of the animal images that I acquired for the museum over the past 30 years. Lively conversations with Professor Itō and passionate debate with other Japanese colleagues became part of the joy and pain of curating an exhibition on such a broad topic. The research and planning for it turned up some surprises, such as the relative scarcity of Japanese works of art in which all 12 zodiac animals are depicted. Although it originated in China, the East Asian zodiac, comprising 12 animals over a 12-year cycle, evolved distinctive features after it arrived in Japan. Every Japanese person knows his or her own zodiac animal, its characteristics, and the other animal signs with which it is most or least compatible. A person born in the year of the boar, for example, might commission in that year a scroll featuring that animal alone, to be hung in his or her tokonoma, the alcove in a Japanese home where art is displayed. Perhaps such a personal connection with one’s own zodiac animal made works of art depicting all 12 animal signs less popular.

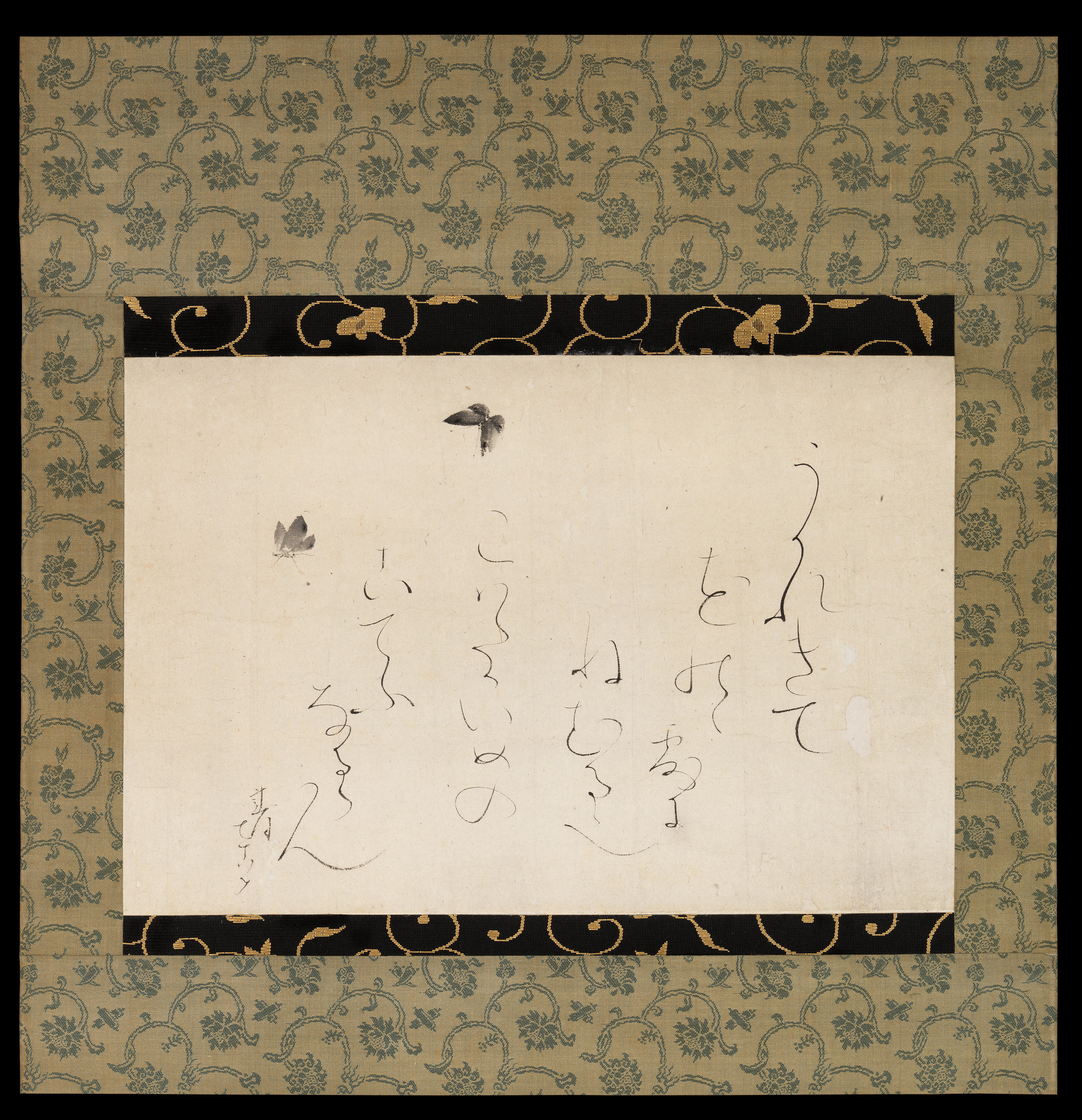

A feature of the exhibition is the strong presence of female artists, some of whom may have been overlooked in recent times. Among the women in this exhibition is Ōtagaki Rengetsu, creator of the hanging scroll Butterflies and Poem. She was so popular in her day that she had to change her Kyoto residence repeatedly to escape her followers, who would line up outside her home hoping to commission a personal painting and poem. A Buddhist nun, Rengetsu was one of many women of the Edo period (1615–1868), a number of them imperial princesses, who pursued their calling as artists. Among these was Her Imperial Highness Princess Teruko, whose superb ink painting of Kannon Bosatsu on a horse bears an inscription that indicates both her gender and her imperial lineage.

Over the centuries, particular creatures acquired meanings so familiar that they functioned as symbolic shorthand—the turtle signifies long life, and the carp ascending a waterfall serves as an example of overcoming an obstacle through great effort. To a Western audience, however, not every artwork so readily reveals its animal nature. A set of incense burners with blooming irises appears to be entirely floral. But to a knowledgeable viewer, the hexagonal shape recalls the six-sided plates on a turtle’s shell, a symbol of good fortune.

If further evidence were needed that animals play an unparalleled role in Japanese art and culture, we need only look to the ways in which that legacy is interpreted in contemporary work, from the fashion creations of Issey Miyake to the sculptures and paintings of such luminaries as Kusama Yayoi, Nara Yoshitomo, and the digital works by the artistic collaborative known as teamLab. All are present in the exhibition.

This exhibition does not presume to supply a definitive reason for the prominent place, however magical and mysterious, of animals in Japanese art. Rather, I hope that the rich array of objects presented here may serve as a lens through which the culture and tradition of animals in Japanese life can be viewed, and thus point the way toward further exploration and the joy of discovery.

Every Living Thing: Animals in Japanese Art is on view in LACMA’s Resnick Pavilion through December 8, 2019. This article was first published in the Summer 2019 issue of Insider.