It’s that time of year when things start feeling spooky! With Halloween right around the corner, we asked some museum staff who worked on the exhibition Fantasies and Fairy Tales to share their favorite fairy tales and an artwork in LACMA’s collection that most reminds them of their selection. Today, Erin Maynes, who curated the exhibition, tells us about her pick. Read on for some Halloween inspiration and check back next week for Part Two.

Erin Maynes, Assistant Curator, Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies

Although "favorite" might not be the right word, lately I've been thinking about the Niebelungen legend, particularly the story of Kriemhild/Gudrun. In Fritz Lang's two-part epic film of the Niebelungen, the second film is titled Kriemhilds Rache, or Kriemhild's Revenge, and is about Kriemhild's single-minded focus on avenging the death of her first husband, Siegfried, at the hands of her brother's loyal vassal, Hagen. Kriemhild’s desire for revenge results in the downfall of the royal houses of both the Burgundians and the Huns and widespread destruction and annihilation, including the death of Kriemhild's family. It is not a fairy tale with a happy ending.

From the first film, Siegfried, to the second, Kriemhild is transformed from the demure, sweet maiden with Leia-like braids into an avenging Fury, rage personified. Margarethe Schön will give you goosebumps and haunt your dreams! Her facial expressions and eye makeup are an inspiration for any who want to throw a killer look with a raised eyebrow now and then. I watched the film again as part of my preparation for the install and in addition to being struck by how beautiful and haunting and well-crafted it is, parts of it also felt timely. It indicates ways that these stories are flexible and durable—we can find our own parts of the story that speak to our times and experience.

Kriemhild’s story feels relevant because of the cultural reckoning we are having at the moment with women's anger—how we deal with it and how women are conditioned to express it. Kriemhild’s rage is transgressive and destructive, but it is also powerful and consequential. Her actions obviously have tragic consequences, but Lang does not paint Kriemhild as a villain. As an interesting side note: the film Siegfried was re-released in the 1930s by the Nazis for its depiction of the Germanic hero, which was further amped up with a Wagnerian soundtrack. But they scrapped the second film about Kriemhild entirely. While the Nazis were able to promote Siegfried as both hero and victim of the German people—and connect his story to anti-Semitic propaganda that cast Germany as the eternal victim of Jews and other imagined enemies—they had no use for Kriemhild, who is no victim.

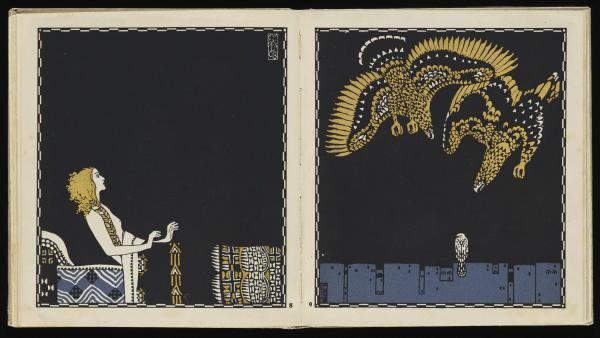

The artwork that reminds me of this story is definitely the book The Niebelungs by Carl Otto Czeschka, on view in Fantasies and Fairy Tales. In the gallery it is open to the page depicting Kriemhild waking from a prophetic nightmare in which a falcon (representing Siegfried) is attacked by two eagles (probably Gunther and Hagen). It's this beautiful Jugendstil illustration in a palette of blue, black, and gold, perfectly suited to the fantasy representation of Kriemhild's dream. You can also see the similarities between the visual style of that book and the sets and costumes in Lang's film.

Fantasies and Fairy Tales is on view in the Ahmanson Building, Level 2, through February 3, 2019.