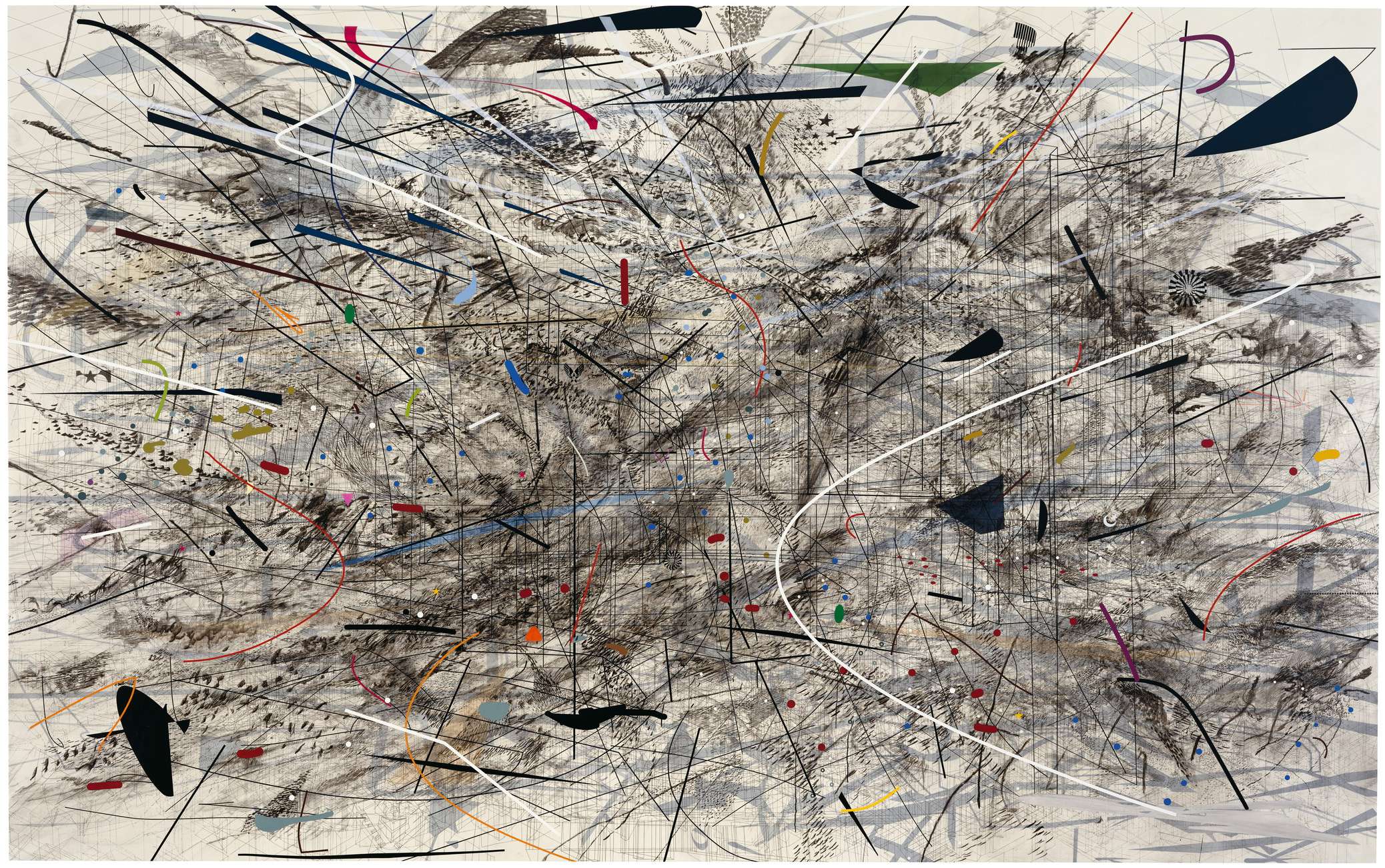

Co-organized by LACMA and the Whitney Museum of American Art, Julie Mehretu is a mid-career survey that unites nearly 40 works on paper with 35 paintings dating from 1996 to the present by Julie Mehretu. The first-ever comprehensive retrospective of Mehretu’s career, the exhibition covers over two decades of her artistic evolution, revealing her early focus on drawing, mapping, and iconography and her more recent introduction of bold gestures, sweeps of saturated color, and figurative elements. Mehretu’s examination of the histories of art, architecture, and past civilizations intermingle with her interrogations into themes of migration, revolution, climate change, global capitalism, and technology in the contemporary movement. Her play with scale, as evident in her intimate drawings and large canvases and complex techniques in printmaking, are explored in depth.

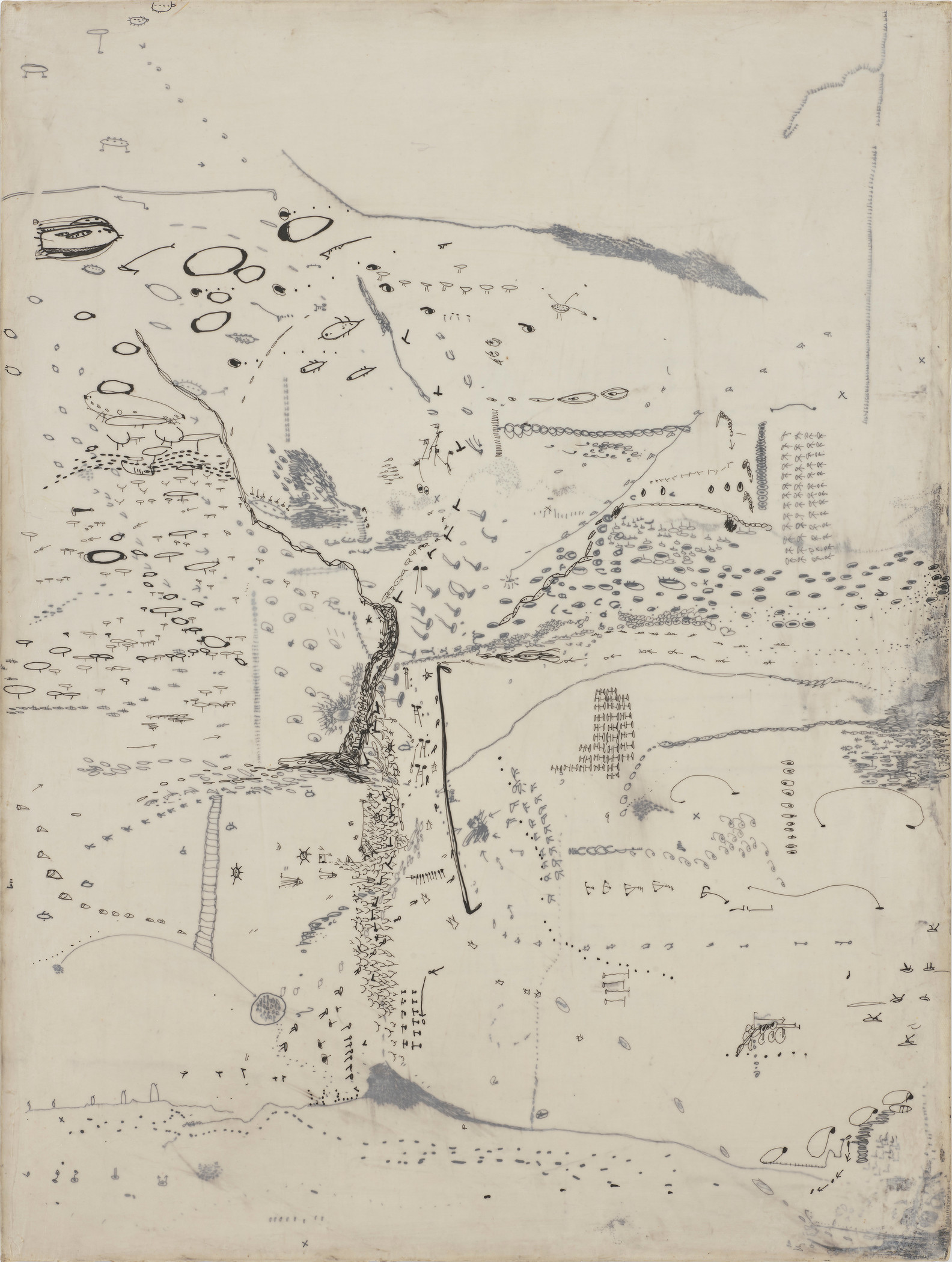

In early works such as Untitled (two) (1996), Mehretu explores how to represent the cumulative effect of time by layering materials. In these paintings, she has embedded drawings between strata of poured paint, creating fossilized topographies.

.jpg)

In Stadia II (2004) and Black City (2007), Mehretu interrogates sports and military typologies to disrupt modern conceptions of leisure, labor, and order. The coliseum, amphitheater, and stadium in Stadia II represent spaces that are designed to situate and organize large numbers of people but also contain an undercurrent of chaos and violence. While Stadia II is filled with curved lines and a panoply of pageantry such as flags, banners, lights, and seating, Black City is more linear and contains references to the military and war, such as general stars and Nazi bunkers. Both works call attention to the ways in which modern culture and the spectacle of contemporary wars, such as the War on Terror and the Iraq War, are connected to imperialism, patriarchy, and power.

On view in BCAM, Level 1, the four-part painting, Mogamma (2012), took major inspiration from the 2011 Egyptian revolution, part of the “Arab Spring” uprisings in the Middle East and North Africa. The work was named after a government administrative building on Tahrir Square that was seen as a symbol of modernism and the country’s liberation from colonial occupation when it was first built in 1949. It was later associated with government corruption and bureaucracy before eventually serving as a revolutionary site. Mehretu began work on Mogamma’s four vertical canvases by exploring the densely layered environment of Tahrir Square, where an array of architectures—including structures built in Islamic, European, and Cold War styles—coexist. She then created a web of drawings that combined the Brutalist architectural style of the Mogamma with details from other public squares associated with the revolutionary fervor of the Arab Spring, such as the amphitheater stairs and spiraling lights of Meskel Square in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and the mid-century highrise buildings surrounding Zuccotti Park in New York. Over this she layered drawings of global sites of public protest and change, such as Red Square in Moscow, and Tiananmen Square in Beijing. Mogamma was installed in Documenta in 2012 and again in London in 2013. This exhibition marks the first time the work has been shown in its entirety in the U.S.

Installed alongside paintings, Epigraph, Damascus (2016) is a major achievement in printmaking for Mehretu, representing a new integration of architectural drawings and painting overlaid with an unprecedented array of marks. Working closely with master printer Niels Borch Jensen, Mehretu used photogravure, a 19th-century technique that fuses photography with etching. She built the foundation of the print on a blurred photograph layered with hand-drawn images of buildings in Damascus, Syria, then composited that together with a layer of gestural marks made on large sheets of Mylar. On a second plate, Mehretu executed her characteristic variety of light-handed brushstrokes, innovatively using techniques known as aquatint and open bite. This work was acquired by LACMA during our 32nd annual Collectors Committee Weekend (April 20–21, 2018).

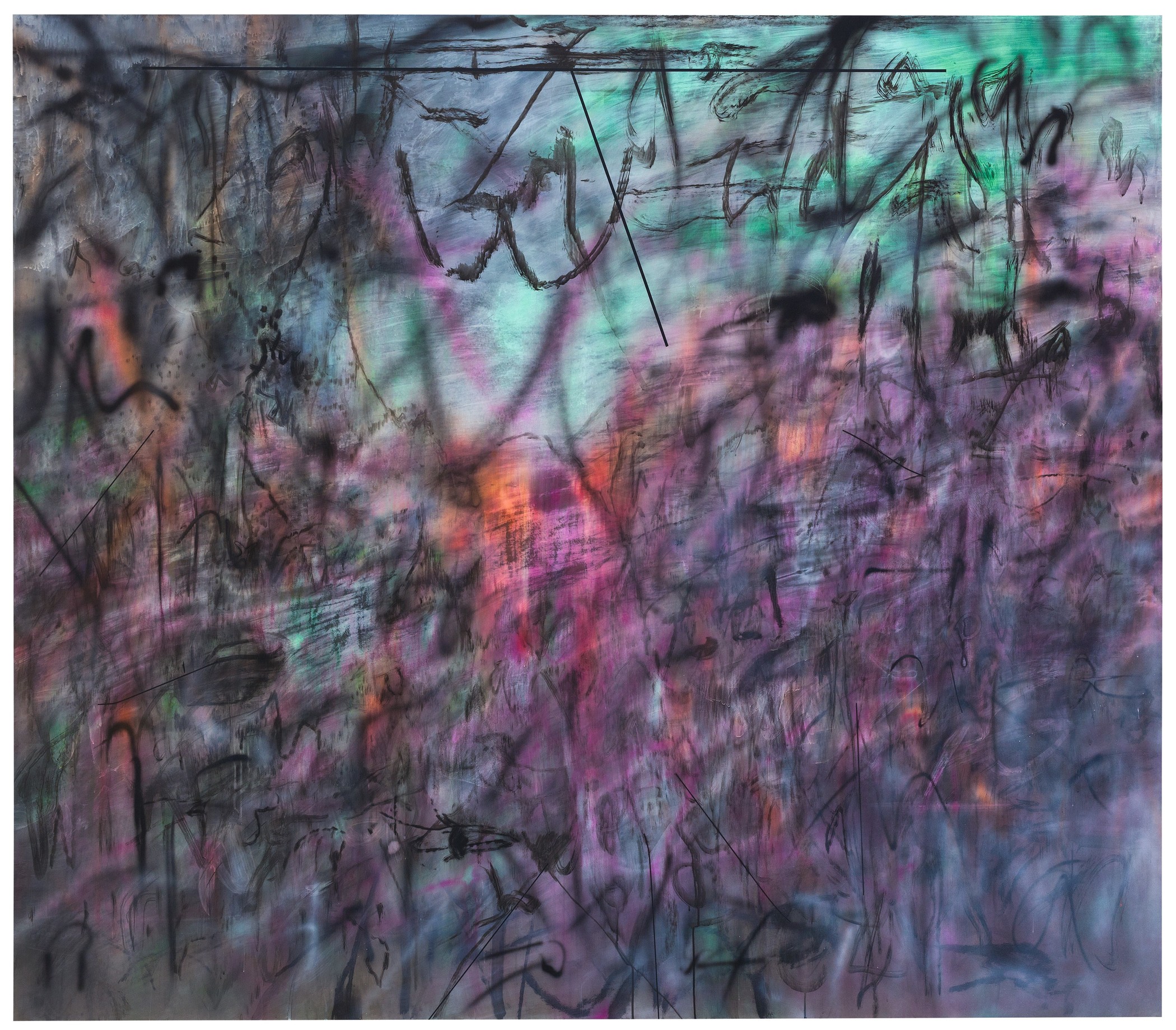

Mehretu’s most recent paintings introduce bold gestural marks and employ a dynamic range of techniques such as airbrushing and screenprinting. The works draw on her archive of images of global horrors, crises, protests, and abuses of power, which she digitally blurs, crops, and rescales. Mehretu uses this source material as the foundation for her paintings, overlaying the images with calligraphic sweeps and loose drawings. For example, Conjured Parts (eye), Ferguson (2016) links disembodied anatomy with a site of violence and political strife. The painting began with a blurred photograph of an unarmed man with his hands up facing a group of police officers in riot gear, which was taken during the protests that followed the fatal shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. Mehretu layered color over a blurry, sanded black-and-grey background. Fuchsia and peachy-pink areas rise from below, while toxic green tones float above like distant skies drawing near. Outlines of eyes, buttocks, and other body parts appear within the graffiti-like marks and black blots that hover over smoky areas, suggesting human activity obscured.

In Hineni (E. 3:4) (2018), Mehretu addresses the environmental blazes caused by climate change, and the intentional burning of Rohingya homes in Myanmar as part of a campaign of ethnic cleansing. The painting is based on an image from the 2017 northern California wildfires, while the word “hineni” in the title translates to “here I am” in Hebrew, which was the biblical prophet Moses’s response to Yahweh (God), who called his name from within the burning bush to tell him he would lead the Israelites to the promised land. By interrogating three types of fires in this painting, one environmental, one intentional, one prophetic, Mehretu explores the contradictory meanings of a single elemental force.

Julie Mehretu is on view in BCAM, Level 1 through March 22, 2020 and BCAM, Level 3 through May 17, 2020.