In May, the Decorative Arts and Design Acquisitions Committee (DA²)—which works with the Decorative Arts and Design department’s curators to help LACMA add outstanding objects to our permanent collection—held its 11th annual meeting. It was a massive success, and all of the remarkable pieces presented were approved for acquisition. Thanks to the generosity of the committee, these works will now join the museum’s collection, ensuring these objects will be an integral part of our initiatives and exhibitions in the coming years. Paul Scott's plates addressing contemporary justice issues are already on view.

In addition to this immense show of support, we were able to raise funds towards the conservation of the Raymond Loewy–designed Avanti, which was acquired by the group in 2014. This ambitious project will be dedicated to the memory of our cherished department supporter Peter Loughrey, who loved vintage cars and LACMA in equal measure.

You can learn more about the newly acquired objects below.

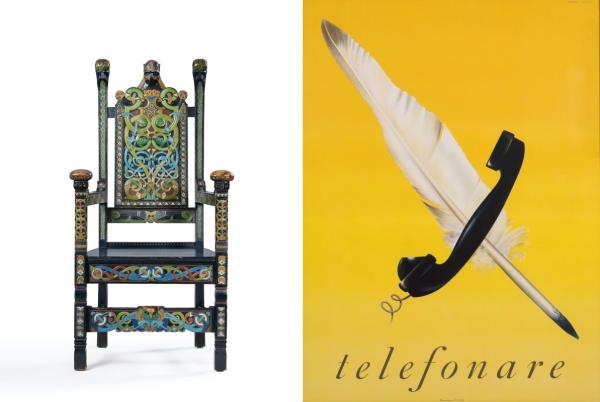

Lars Kinsarvik

Armchair, c. 1905

Described by scholars as “the most important creator of the Norwegian style in woodworking” and “the most imaginative and skilled artist of the Viking revival,” Lars Kinsarvik was a champion of Norwegian national identity in the decades around 1900. Like many practitioners of Arts and Crafts movement ideology, Kinsarvik adopted the imagery found in medieval churches and vernacular traditions. However, the British reformers’ repugnance towards the ills created by industrialization was not shared in largely agrarian Norway. While adhering to Arts and Crafts moral aesthetics, the “simple life,” and the handmade, leaders such as Kinsarvik created furnishings that served more as a declaration of their country’s cultural autonomy.

This majestic chair is a tour de force of Kinsarvik’s Viking revival style. The head of a fierce warrior, flanked by two other faces, dominates the crest rail; complicated polychromed interlace patterns adorn every surface except the seat.

John Vassos, Radio Corporation of America (RCA)

Portable Phonograph, RCA Victor Special, Model M, c. 1935

John Vassos is an underrecognized hero of American industrial design. As the lead designer for the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) between 1932 and 1975, he left his imprint on almost every new electronic device in the modern home, especially radios and television. One of his most iconic creations, however, is this portable phonograph, which epitomizes new technology as well as the aesthetic of streamlining.

The qualities of speed, power, and dynamism inherent in new forms of transportation were brought into a domestic setting during the Great Depression. Streamlining was the ultimate expression of machine imagery (rather than the machine form beloved by practitioners of the International Style). This phonograph’s horizontal lines suggest forward motion; its smooth surfaces imply rationality and control, reassuring qualities during a period of economic trauma. The new, lightweight materials Vassos used here—aluminum, chromium-plated steel, and plastic—were essential to both the phonograph’s visual language and to its function. The reflective sheet at the back, for example, enabled people to watch the records spin while providing a storage space for more discs. Versatility was the great innovation—powered by a hand crank, the phonograph could be used in any room or outdoors, with its suitcase shape emphasizing portability. While others at RCA developed the phonograph’s ingenious engineering, it was Vassos who ensured its success with his concern for users and creation of visual allure.

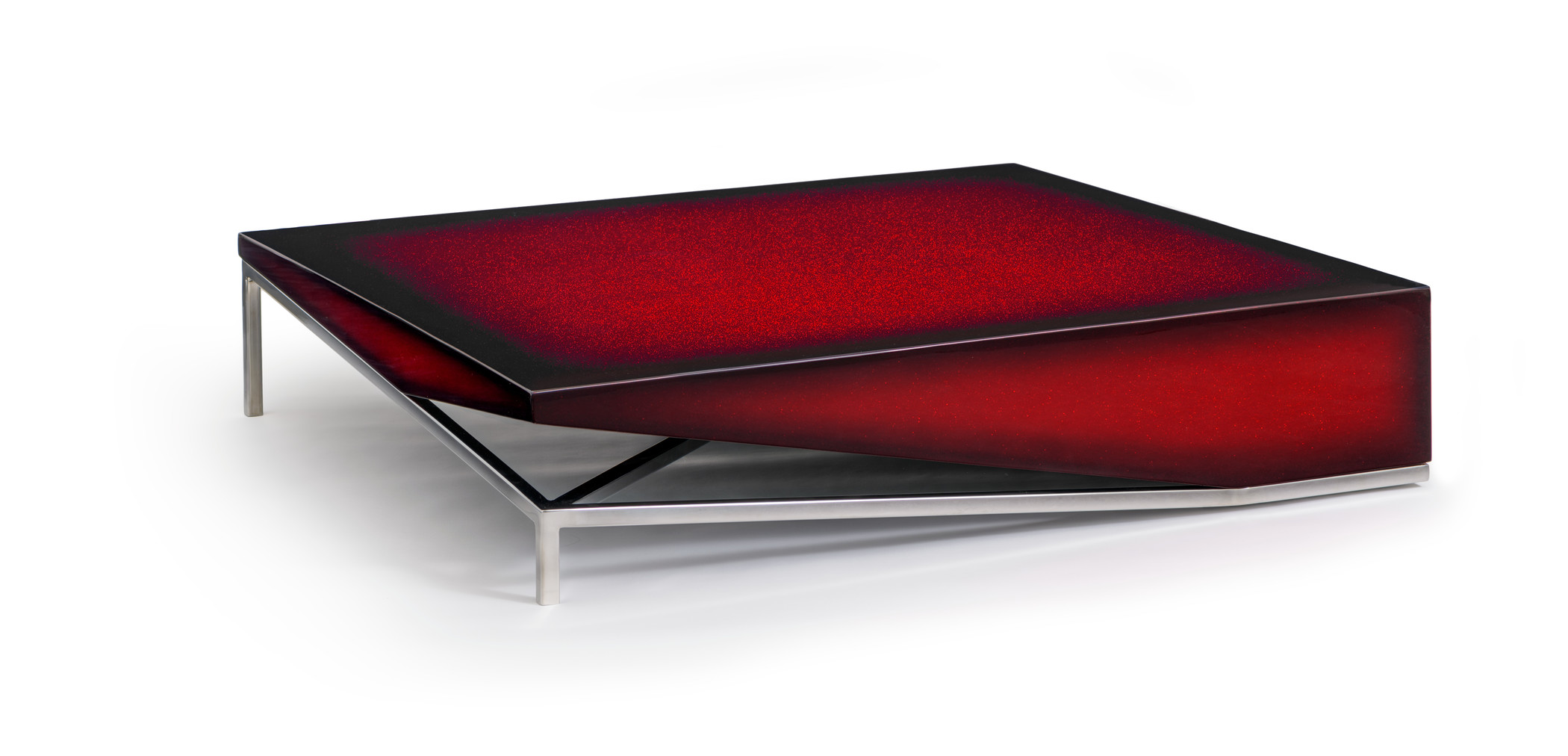

Ini Archibong

Switch table, designed 2011

Los Angeles–born, Switzerland-based designer Ini Archibong is known for combining exquisite materials with impeccable craftsmanship, and strives to imbue his objects with the spirituality he derives from both his Methodist upbringing and independent study of Theosophy. The Switch table represents early efforts to synthesize these ideas and practices.

The table emerged from an ArtCenter furniture design class assignment to create a coffee table. Archibong sought to make a piece of furniture that reflected his personal experiences without sacrificing functionality. He envisioned a coffee table inspired by the lowriders he saw on cruise nights in the Crenshaw District. The table that resulted appears to be in motion, like a lowrider with two wheels touching the ground and two rising in the air. The name of the table derives from the practice of “hitting switches,” where drivers activate the hydraulic system to make the car rise and fall. Through the Switch table, Archibong celebrates lowrider culture, translating the subversive acts of occupying city streets with flamboyant cars into a static object that appears to be in continual motion.

The mesmerizing tabletop has a complex crystalline surface comprising multiple layers of metal flake, with a top layer of burgundy-to-candy-red fade. The asymmetrical base and the rich, mutable color of the surface gives the sense of perpetual motion and reflects Archibong’s interest in visual perception of color and light.

Ryan Preciado

Nipomo chair, designed 2018, this example 2022

Chumash chair, designed 2019, this example 2022

Ryan Preciado’s Nipomo and Chumash chairs represent the powerful ways that furniture can express the creator’s values and experiences. His inspirations include lowrider culture, skateboarding, jazz, and his Chumash heritage. Born in Los Angeles, Preciado grew up in Nipomo, on California’s central coast.

The Nipomo chair derives from Preciado’s childhood experiences, when he spent time at his maternal grandmother’s house and garden. Donna Toluga Nuñez was very proud of her heritage, running a Chumash cultural center in Guadalupe, California. Her garden seemed huge from the vantage point of a child, a vast wonderland ripe for endless exploration. The almost cartoonish scale of the chair recalls the feeling of being in that abundant space. He reads the fabric (created by fashion designer Raf Simons for the Danish firm Kvadrat) as a field of flowers, reminiscent of the garden. Preciado’s utmost aim is to make furniture that connotes warmth and comfort—the abstracted floral fabric creates the sensation of immersion in a lush garden.

The Chumash chair was intended as a conscious appropriation of a European-American form. Preciado borrowed elements from Danish designer Børge Mogensen’s Spanish Chair (1958), a Spanish/American/Danish mashup, and “Indigenized” it, imparting characteristics of his own Chumash culture. He made the chair taller to create more grandeur and changed the arms to a half-moon shape similar to the oars of Chumash canoes. By renaming it, he reinforces the appropriation, and claims Native dominance over a European form (which was itself borrowed from colonial Americans).

Anina Major

The Eye, 2021

Bahamian artist Anina Major explores themes of identity, migration, and craft in her beautifully woven ceramic sculptures. Major’s grandmother taught her how to braid straw baskets when the artist was a child. Though often derided as women’s craft made for tourists, plaited straw objects have a centuries-long history that originated among the island’s Indigenous and enslaved West African populations. Major’s Plait series honors this tradition by recreating the technique in the enduring medium of clay. As she said in an interview: “The objects my grandmother made will deteriorate. They are made from the tree palms. There’s something beautiful about me taking that practice and putting it into an object that will exist as some kind of evidence that we were here.” The open, woven form of The Eye evokes a tropical storm, suggesting both the strength and fragility of the artist’s native country.

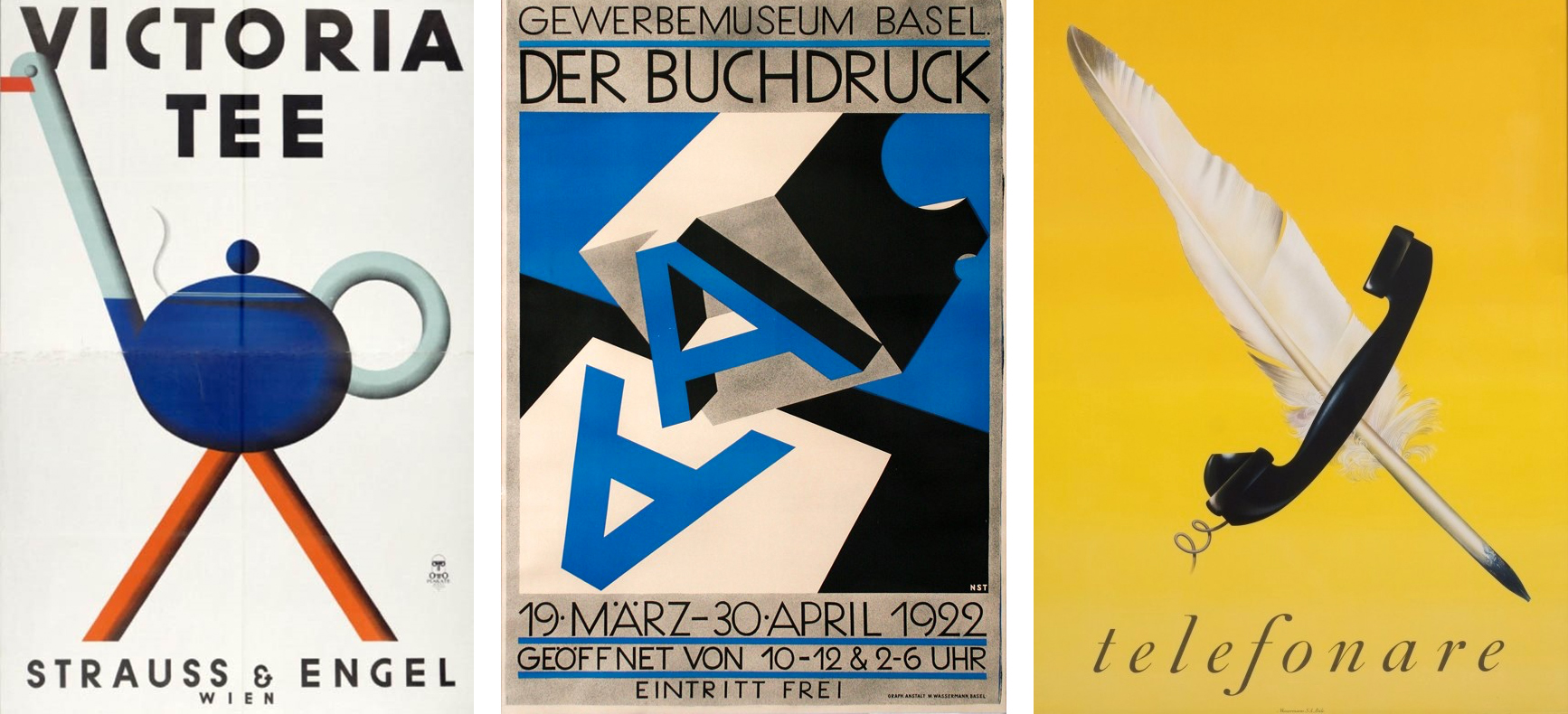

Otto Löbl

Victoria Tee, 1926

Niklaus Stoecklin

Der Buchdruck, 1922

Herbert Leupin

Telefonare, 1941

These three posters demonstrate the innovative advertising style known as Sachplakat (object poster). Developed in Germany in the early 20th century, Sachplakat presented items in isolation, often with little more than the firm’s name for context. The technique established a link between the name and product, a crucial leap as modern consumers adjusted to buying nationally branded products rather than bulk goods that they could see and touch.

The 1926 poster for the Strauss and Engel company’s Victoria Tee was created by Reklameatelier Otto, one of the most successful commercial art studios in Vienna in the 1920s and 30s. The poster cleverly integrates a teapot into an abstracted image of an ostrich (strauß in German), a reference to the company name.

Niklaus Stoecklin’s clinical, realist style reflects the influence of what became known as Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) in Germany, and in 1925, Stoecklin was the only Swiss artist included in the Mannheim exhibition that gave the style its name. Der Buchdruck (The Letterpress) advertises an exhibition of letterpress printing with a single piece of meticulously-rendered metal type in action, commanding attention with bold blue ink and dynamic angles.

Herbert Leupin gained early success with photorealist representations before shifting to a whimsical, cartoon style in the late 1940s. Telefonare (1941) demonstrates his technical skill as well as his subtle, surrealist humor. Here, Leupin wordlessly advertises the efficiency of modern communication by using a telephone handset to cross out an outmoded quill pen.

Walter von Nessen, Nessen Studio

Standing floor lamp, c. 1928

This lamp is a radiant ode to electricity created during the decade of the grid’s most robust expansion. Straddling a transitional moment in both infrastructure and culture, the designer Walter von Nessen employed the new materials and machine age aesthetics that heralded the radical transformation of the American home.

Chromium electroplating underscores the message of a bright future. When the lamp is illuminated, its glinting surface appears charged. This effect was achieved through electrodeposition, a process favored by the designer that had only become commercially available four years prior to the lamp’s production date. At the time, this technology was lauded as “magic,” “impervious,” and “indestructible,” according to the New York Herald Tribune (1930).

Von Nessen called working in chromium one of his joys—his greatest prowess was creating the careful drama of illumination. With its bulb safely cocooned to diffuse glare, the lamp directs a vertical cascade of light. These decisions reflect contemporary beliefs and anxieties about the scientifically correct use of artificial lighting.

Snuffbox in the shape of a dog, c. 1740–50

In the 18th century, Dresden’s talented carvers of semi-precious stones created stunning works by incorporating the naturally occurring patterns of the Saxon region’s minerals into their designs. This exquisite snuffbox in the shape of a pug dog is an especially fine example. The stone specimen was carefully selected for the shape and distribution of its dark inclusions to evoke the hound’s irregularly spotted fur. Although such motley markings have now largely disappeared through selective breeding, the pug dog depicted here is still recognizable through its characteristically wrinkled and compressed countenance. This is a highly original piece that demonstrates the extraordinary harmony achieved between subject and materials in one of the medium’s most important centers of production.

Paul Scott

California Wildfires, 2019

Souvenir of Shiprock, 2020

Forget Me Not, No Human Being is Illegal, 2019

Scott’s ongoing project New American Scenery subverts idealized depictions of the United States on 19th- and early 20th-century blue-and-white transfer printed plates that had been made in England for the American market. These three examples confront, respectively, the subjects of climate change, uranium mining’s impact on Indigenous communities, and immigration—all as they pertain to the American west. For California Wildfires, Scott partially erased a souvenir plate, adding flames to highlight how the state’s “beauty spots” and monuments are threatened by climate change. Souvenir of Shiprock is decorated with images of Scott’s trip to northern Arizona and New Mexico, with the most prominent being a portrayal of his host, the activist Timothy Benally, standing outside the Office of Navajo Uranium Workers. On Forget Me Not, No Human Being Is Illegal, the disturbing loss of life in US/Mexico border crossings is represented in the border of the plate, while a quote from Nobel Peace Prize winner and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel is at its center.

These three plates are on view in the exhibition Conversing in Clay: Ceramics from the LACMA Collection.