In the last four decades, the increasing ease and accessibility of image editing softwares have transformed the visual world, enabling new forms of creativity and sparking philosophical debates about the very nature of representation. This fall, LACMA is exploring the impact of this technological shift in the PST ART: Art & Science Collide exhibition Digital Witness: Revolutions in Design, Photography, and Film. By integrating simultaneous developments in the fields of graphic design, photography, and visual effects, the exhibition demonstrates the pervasiveness of digital manipulation tools, tracing the emergence of distinctive digital aesthetic strategies and examining how they have altered the patterns, flow, and stakes of visual communication.

Digital Witness features over 150 works, placing photographs, posters, publications, installations, and video works in dialogue with moving image files, feature film clips, advertisements, and music videos, demonstrating how these tools have impacted both creative practice and daily life. The exhibition includes a diverse, international group of makers, from established digital pioneers like Cory Arcangel, Andreas Gursky, and Andy Warhol to emerging voices like LaJuné McMillian, Miao Ying, and Kyuha Shim.

Among the influential figures whose contributions are included in the exhibition is Casey Reas, an L.A.-based artist who approaches software as an artistic medium. In his work, software becomes a collaborator generating new imagery, rather than a tool to realize the artist’s set vision. He has long advocated for artists’ active participation in coding and in 2001, he co-initiated Processing, an open-source programming language and environment for the visual arts, with his collaborator Ben Fry. His work has been collected by LACMA and last year, his generative artwork An Empty Room (2023) was on view at the museum. The Q&A with Reas excerpted here is one of 12 interviews with artists, designers, and filmmakers featured in the exhibition’s catalogue. The illustrated 256-page book also includes an introduction and six essays that each look at aspects of digital aesthetics, tools, and labor.

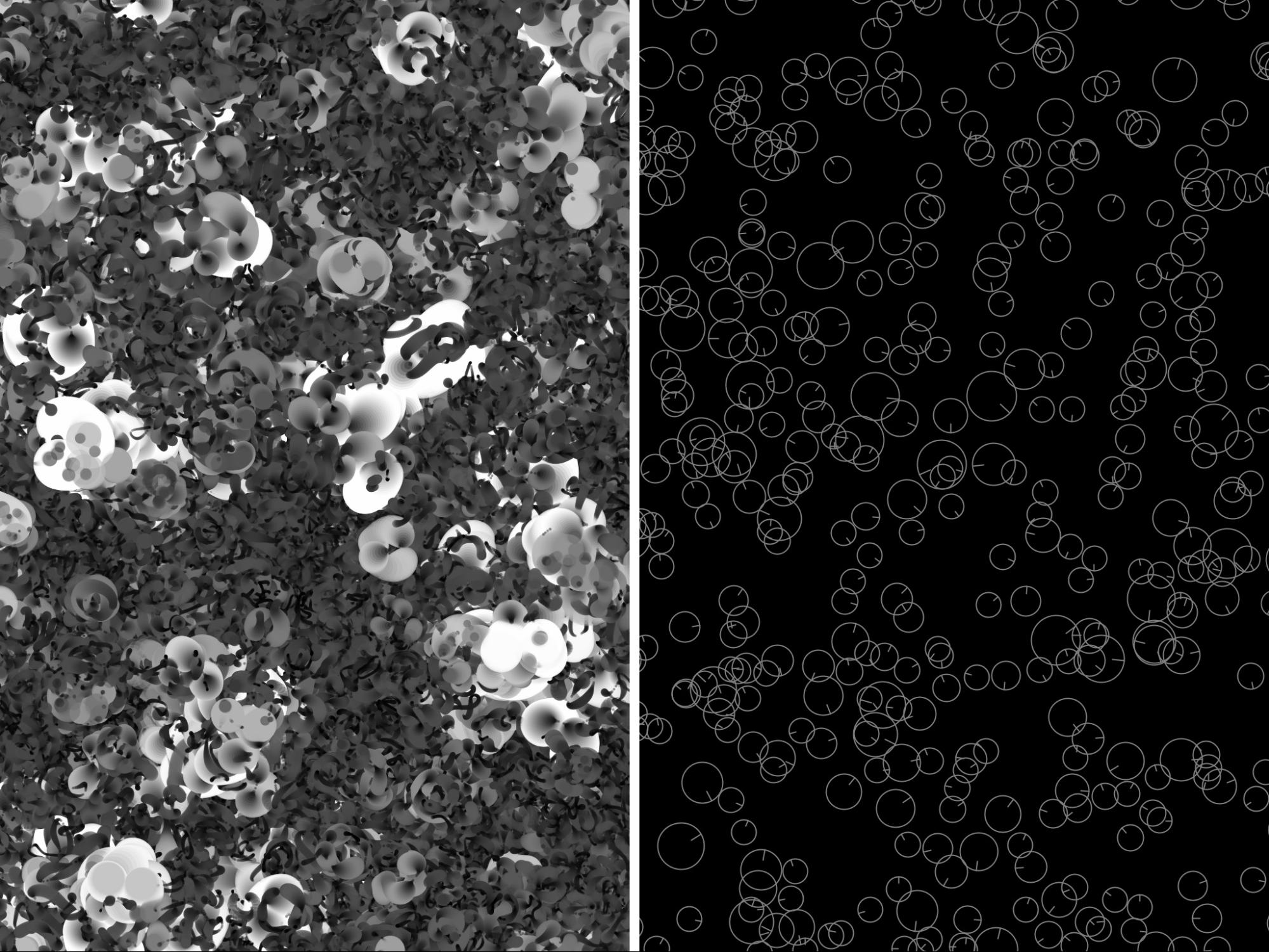

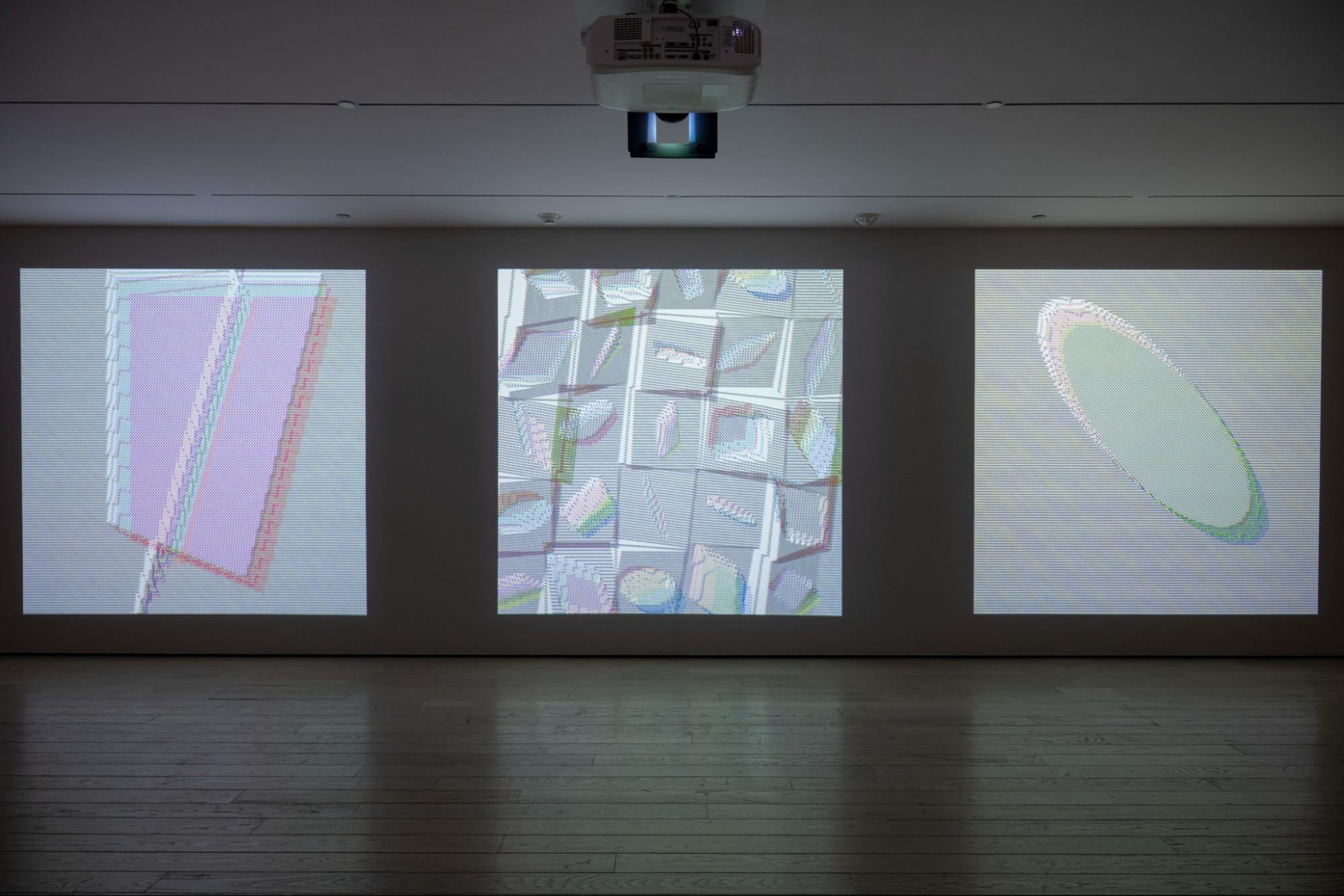

A preview gallery of Digital Witness, featuring Reas’ Process 14 (2008) and work by a selection of other artists, is now on view in BCAM, Level 1. The full exhibition opens November 24.

How did digital tools change your working practice? Were there things you could do digitally that had previously been impossible (or extremely difficult)?

Learning to code when I was in my late twenties was the breakthrough for me. I was no longer reliant on digital tools other people created; I made my own tools. With this control, I was able to follow my specific direction. My work could be more precise and unique. I no longer needed to fit my ideas into someone else’s mental models and constraints. Learning to code isn’t technical; it’s conceptual. It expanded my ability to think. With that, new ideas emerged. I’ve been following these ideas for 20 years now, always expanding what I imagine to be possible, always discovering new paths. The kind of work I create isn’t possible with other media. My work is related to animation, video, painting, drawing, photography, and choreography, but it extends into durational, nonlinear performance. Learning to code allowed me to transition from making pictures to making systems. Now I create a system, and the system creates pictures. It’s a form of abstraction, but it’s conceptual, not visual, abstraction.

What is gained/lost when a process moves from analog to digital?

I think when we can combine analog and digital, we can do more than either can alone. For example, I taught a one-week summer workshop at the Anderson Ranch Arts Center in Snowmass, Colorado, in 2018, exploring this in depth. We were working back and forth in a computer lab and darkroom all week. Images started in the darkroom or with code and then migrated to the other. I’m part of the generation of people who spent the first years in art school with analog media, then shifted to digital halfway through. I’ve always worked in both. I always try to see the pros and cons of moving to the digital realm and also the potential of synthesis. Right now, I’m collaborating with Erika Weitz to make wet-plate collodion images from machine-learning AI images. This combines the current state of image synthesis with one of the earliest forms of photography. The results are beyond my expectations. The infinite resolution of analog media is even more incredible after working with the constraints of digital images for so many years.

Is there a “digital aesthetic”?

I think digital images have a surface that’s analogous to timbre in music. For example, a Bach keyboard work can be played on harpsichord, piano, or synthesizer. It’s the same sequence of frequencies, but the way the work is experienced changes with each instrument. Different digital technologies are specific instruments to feel visual artworks. For instance, changing the rendering engine for a 3D file changes the experience of the digital sculpture. I think there are many digital aesthetics that work with photography, 3D rendering, and digital painting. The technology is always present in both analog and digital materials, whether that’s a specific kind of paint or a specific dithering algorithm (a way of approximating a continuous-tone grayscale image, like a photograph, with black and white pixels). Low resolution was a condition of early digital media by necessity, but now it’s an effective signifier that’s amplified to read as “digital.”

My idea of digital aesthetics involves working with time, change, and nonlinearity. For me, digital art is a kind of performance medium. Generative digital work is created within the moment, like music. A painter, for example, will create work in the studio, then it’s later seen in the gallery. A composer and a generative artist will create a score in their studio, but the work is performed in the salon or gallery. There’s no distance between the work being created and experienced. Generative art can also be nonlinear and continuously changing. For example, in most of my work, I don’t know what’s going to happen in the next minute, the next hour, or the next day. I’m as surprised as anyone else when I look at the work. Digital aesthetics move beyond the still image and beyond linear image sequences that were paramount before digital media.