The exhibition Sam Francis and Japan: Emptiness Overflowing, currently on view at LACMA through July 16, contains more than 35 prints made by Francis in various techniques including lithography, etching, woodcut, and screenprint. Printmaking was central to his overall artistic practice starting in the early 1960s. It allowed for the layering of translucent colors that he aspired to in his paintings and may even have influenced his manner of painting horizontally (since prints are usually created on a flat plane). In describing his interest in the medium, however, Francis alluded to printmaking’s intangible quality, rather than its technical aspects, stating simply that “there was a certain amount of magic about it.” The artist’s attraction to this “magic” resulted in the creation of more than 500 fine print editions in his career. While Francis was a global artist who lived and worked in Paris, New York City, and Tokyo, his primary base was Santa Monica from 1962 until his passing in 1994. As a result, the majority of his prints were made in Los Angeles where he worked at the city’s famed workshops Tamarind and Gemini G.E.L. (as well as the shorter-lived Joseph Press) and founded two print workshops of his own—the Litho shop in 1970 and Lapis Press in 1984.

Among Francis’s earliest prints were those made at the landmark Tamarind Lithography Workshop founded by artist and printmaker June Wayne in 1960 and a hub for contemporary lithography until 1970 (when it moved to Albuquerque). Lithography dominated Francis’s printmaking activity in the 1960s. He worked almost exclusively with tusche (a greasy black liquid) that allowed him to use a brush to compose the image on the stone, much as he would apply paint to canvas. In Untitled (1963) [top image], for example, Francis used the fluid medium to make bulbous forms and drip marks to create this visually animated image that was then chemically fixed and a sheet of paper passed through the press four times (for five colors). A few years later he returned to Tamarind to create prints related to his Edge series, like Blue Cut Sail (1969) [above], which encompasses the white of the paper as an essential part of the composition “framed” by ribbons and droplets in tusche.

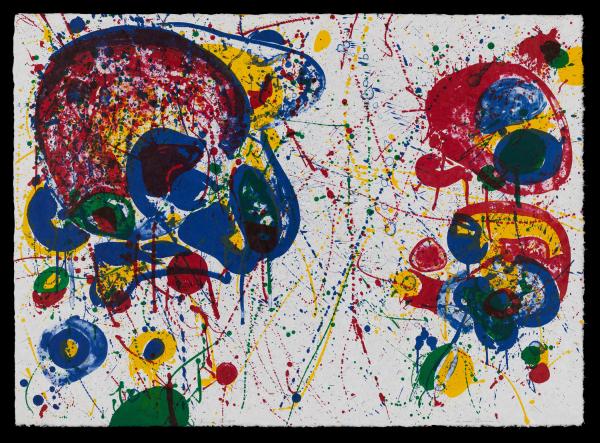

Tamarind also had a training program for printers, many of whom went on to set up their own workshops like Joseph Zirker and Joe Funk who established Joseph Press in the mid-1960s. Francis worked with Zirker and Funk to make 10 of the lithographs included in the Pasadena Box [above], a multipart set commissioned from Francis by the Pasadena Art Museum (now the Norton Simon Museum of Art) as a fundraiser. It represents a compendium of the artist’s visual vocabulary in the mid-1960s—suspended ball forms and fields of splatter in mostly primary colors—with three of the prints mounted on a small folding screen and one on a hanging scroll in Tokyo in the manner of established Japanese painting formats.

In 1971, Francis made his largest print to date at Gemini G.E.L., a workshop founded in 1966 by Ken Tyler, Stanley Grinstein, and Sidney Felsen and known (still today) for its ambitious and technically-advanced approach to printmaking. Spleen (Red) [above at left] measures more than six feet across and, despite the visceral associations of its title, suggests an ethereal and color-infused passage indicated by the artist’s bold use of space. The scale is ambivalent, with allusions to both microscopic and cosmic realms, pointing to the artist’s interest in oppositions. According to the artist, oppositions “...give a real presence to the universe. This is what it is all about! Opposites are just the root, a kind of path, or a way to being more alive or conscious.”

Meteorite (1986) [above], a monumental screenprint also made at Gemini, is another example of Francis’s expansive vision that captures the cosmic energy suggested by the title and enhanced by his use of color (32 colors to be exact). In fact, Francis considered color to be the fifth element based on his understanding of Eastern cosmology. In his words: “Fire and air give birth to color, which is another element.”

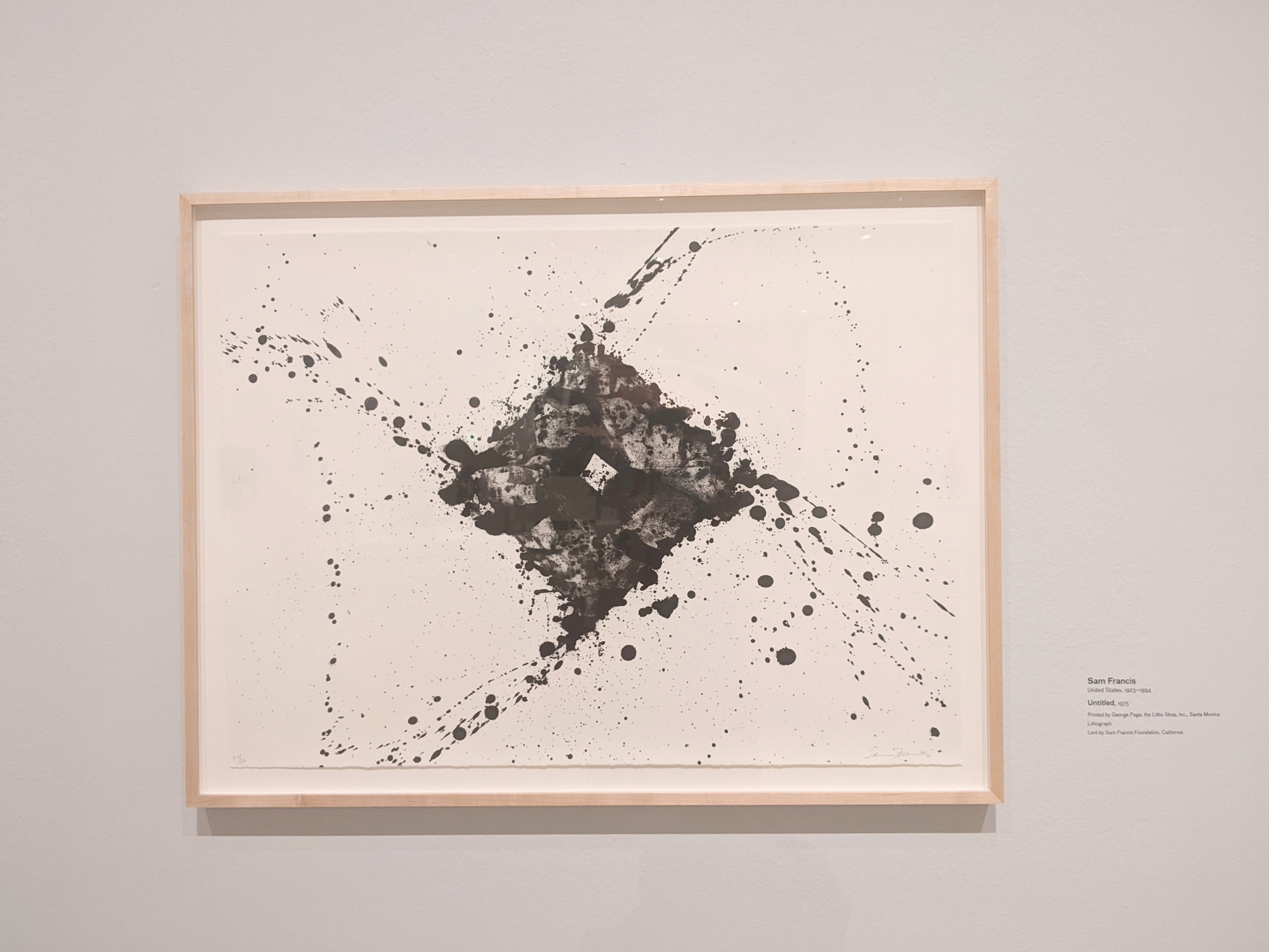

The making of such ambitious prints often required collaboration with a team of printers and hours spent away from his studio. In 1970, in order to incorporate printmaking more regularly into his practice, Francis established the Litho Shop located near his Santa Monica studio. As author of the artist’s print catalogue raisonné, Connie Lembark, explained: “Freedom was perhaps Francis’s primary motive in establishing the Litho Shop—the freedom to come and go as he pleases and to work with people he admires.” For the first couple of years he worked with printer Hitoshi Takatsuki who, after returning to Japan, was replaced by George Page, who would work with Francis for more than 20 years on nearly 100 lithographs (like Untitled from 1975 [above]). In 1981 the Litho Shop expanded to include intaglio (aquatint, in particular) not long after Francis met Jacob Samuel, who was working as an etcher at Gemini. Their collaboration lasted 18 years and produced 120 prints. Among them was Untitled (1989) [below], which involved 24 colors and raw powdered pigments that were sprinkled onto the inked plate prior to the third and final run through the press for a total of 18 variants.

Lapis Press was founded by Francis in 1984 as an enterprise to explore the artist’s multiple and varied interests in poetry, fiction, contemporary art, philosophy, literature, and Jungian psychology. Most of the publications were in the form of bound books that often included lithographs or etchings in the tradition of livres d’artistes. The scope of Lapis’s projects has changed over the years but the workshop (now based in Culver City) continues to be a dynamic center of printmaking activity.

As an avid printmaker (as well as a publisher), Sam Francis contributed greatly to making Los Angeles a center of print culture and appreciation. Don’t miss the opportunity to see Francis’s numerous prints (as well as paintings and works on paper) on view through July 16.