Among the foundational figures whose contributions are on view in Digital Witness: Revolutions in Design, Photography and Film is April Greiman, who helped to define the computer aesthetic in design in the 1980s and has continued to embrace new technologies in her explorations of space and color. In keeping with her multi-disciplinary practice, Greiman’s work has been collected in multiple LACMA departments, with holdings that include groundbreaking posters and publications (including some for LACMA exhibitions) and her more recent photography.

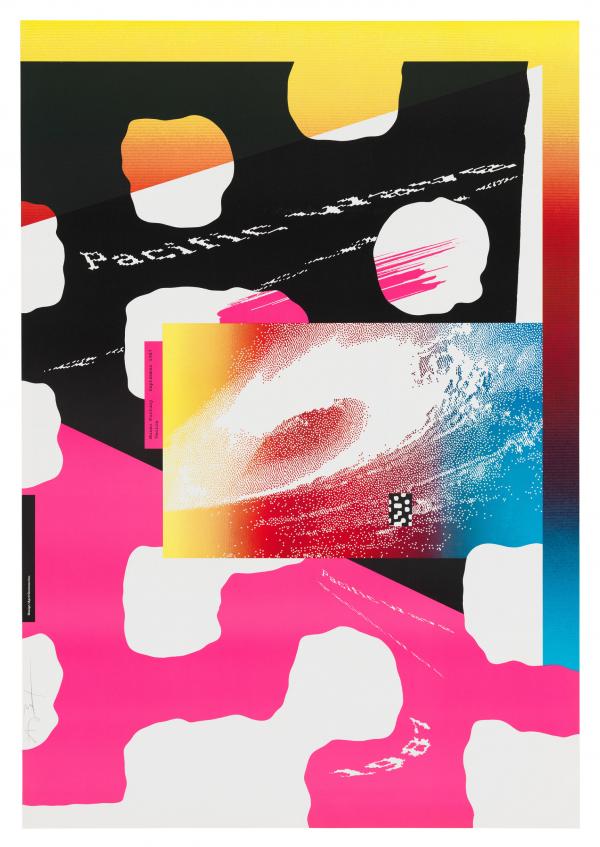

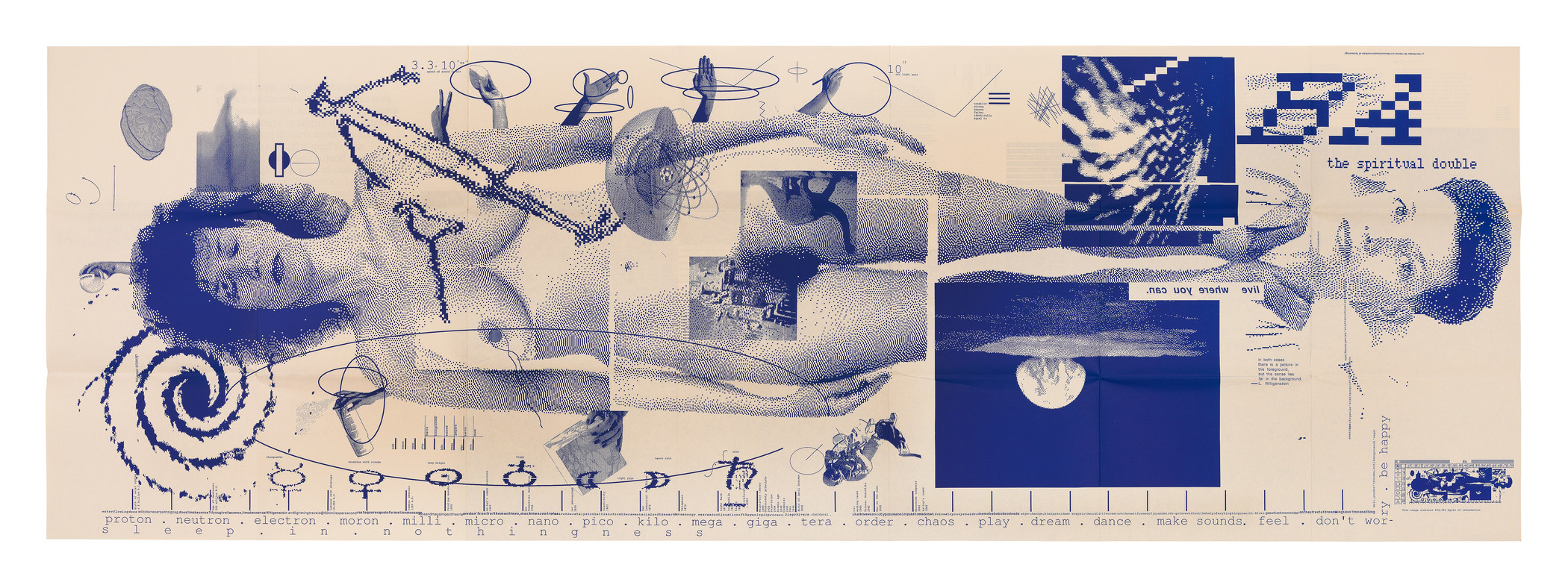

Greiman’s Does It Make Sense? (1986) explores the relationship between human and machine. She answered the question in the title with a statement from philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein: “If you give it a sense, it makes sense.” The work’s scale and intricate detail stretched the limits of the processing power of Greiman’s early Macintosh, forcing the artist to confront both the freedom and restrictions of her chosen tool. In recent years she and her team at Made in Space reimagined this icon of 1980s digital design with 21st-century technology, creating an augmented reality version of the work in collaboration with Isovist, led by Dale Herigstad. Visitors can experience alt<dq (a nod to the work’s original existence as an issue of the publication Design Quarterly) in 360 degrees in Digital Witness. The work is also accessible through a smaller version of the poster available at the LACMA Store, which also produced a facsimile of Greiman’s Pacific Wave (1987).

The Q&A with Greiman excerpted here is one of 12 interviews with artists, designers, and filmmakers featured in the exhibition’s catalogue. The illustrated 256-page catalogue also includes an introduction and six essays that each look at aspects of digital aesthetics, tools, and labor.

What is your earliest memory of manipulating digital images?

Most people see me as one of the first graphic designers to put the Mac [original 1984 Apple Macintosh] into play, but my interest in emerging technologies began well before then. From 1982 to 1984 I was the head of the design program at the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts). I worked on my own explorations in the film-video school at night, with professional video and analog computer equipment that artist Nam June Paik had set up (he was one of the inaugural faculty at the school). I bought my own professional video equipment and started getting commissions in motion branding and advertising (for Esprit Kids, Lifetime, US West, and so on), but my work with computers really took off when I discovered the Quantel Paintbox. My experience there gave me a sense of how computers think and how my world was becoming or would soon be hybridized.

How did digital tools change your working practice?

Any time a new technology is introduced, it usually wants to imitate or mimic a prior technology. For example, when video was introduced, it was said, “That’s the end of film and photography!” But for me it was an entirely different animal, and I gravitated toward trying to figure out what the new technology was, how to think about it, what it “be.” I was really interested not in making low-resolution (video-quality) images look like they were high-end photography, but rather in allowing images to retain their own “texture.” I would juxtapose high-quality, hand-set typography against non-postscript or bitmapped-resolution type, or the coarseness of a still video image against a really exceptional-quality Hasselblad photograph.

After a while, I began to understand basically the way a computer “thinks,” and I deliberately revealed the texture of technology, allowing these textures to be in “conversation” with one another. Something else evolved at that point; it came as such a surprise, and a beautiful thing, because I couldn’t name it. I couldn’t call or designate it as anything. (I feel it is the death of something when it is classified, named, or categorized.) Emerging technology was provocative for me, challenged me to think about space and hierarchies of information. For me, it was playtime.

How has digital image-editing software changed our visual world?

One might see my work as roughly evolving in the following way: early on, I tried to open up graphic design so that it functioned like a field, with different, often unexpected elements in dynamic interaction on a more or less flat surface. I then worked to open this up further, into what I call an environment, a three-dimensional world, that allows for depth and movement. In my current work, I give that environment a kind of atmosphere, which includes an affective and intimate and sometimes even mysterious dimension—atmosphere being the most elusive and, in a way, seductive. All of these are attempts at deepening texture, making sensual. Because atmosphere is the most ethereal, it’s perceived directly but also at the margins of consciousness. We don’t even process it until we’re in it, and then we’re just in it and forget about processing it.

I stopped calling myself a “graphic designer” in 1984 (which, by the way, most likely didn’thelp my business). By that time, if you would say that you were a graphic designer, people would respond saying, “Oh, you do silkscreen prints,” or, “You work from home.” I began using the title of “trans media designer, artist.”

Digital Witness: Revolutions in Design, Photography and Film is on view in BCAM, Levels 1 and 2, through July 13, 2025.